by

Hugh Tucker

11th September 2020

A quarter of a million people use Waterloo station every day. This huge number is hard to fathom, but stand by the escalators and watch, look past the people hauling split plastic bags, suitcases and instruments into the bowels of the city, or the groups of lads holding a quartet of cans and the tourists worriedly watching the departure boards and you’ll see people standing still, waiting patiently as they anticipate pulling away from the city.

One Friday morning I was among them, my ticket in my palm and my mind already on the path I walk when the urge to leave strikes: one that leads to the familiar comforts of my childhood home. I’ve walked it half a dozen times and it’s forged an association in my mind so opposed to my central London neighbourhood that the memory of it is ethereal, but real nonetheless. It’s a drover’s road; a thin stretch of land trampled into permanence centuries ago. It’s easy to overlook now, a subtle influence on a landscape we’ve now cut and filled with concrete, but to stamp your mark on the earth with only your feet feels more special than doing so with the help of ten tonne vehicles and an army of men and women in fluorescent vests. To walk it is to step back through time, and out of the day-to-day.

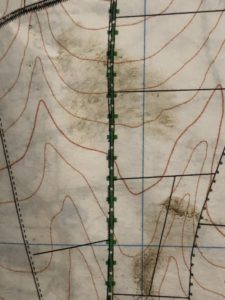

I’d discovered it almost by chance. Long ago I’d toyed with the idea of walking from the closest city to the village I lived in and had spent hours poring over maps. Slowly piecing the network of footpaths together in a sprawling puzzle, I spotted a seam of small crosses running true across the paper indicating a byway. I walked it, once, twice, a third time and now, when I leave my home in London and come back to visit my parents, I walk these dozen miles home.

I’ve taken the same train back to my family’s home so many times that I have developed my own mental strip-map of landmarks. The train ran alongside tall glass buildings, thinning industrial yards and then to red brick houses as we ploughed out of the city. We raced across bursts of open ground, threaded with roads and the occasional concrete bridge, coated in spray can art with a bigger audience than any piece at the Tate. Commuter towns, judged solely on their proximity to a mainline station and travel time to Canary Wharf, came and went, their platforms barren at midday, and then we were out, clear fields to the horizon.

Closer we came, past the Lightning Tree, its twisted trunk cracked by a storm, past a lonely cluster of houses, and the steep field where sheep graze at a forty-five-degree angle. For twenty seconds I watched a farmer carve furrows into the earth. Finally the train slowed in anticipation of my stop: an industrial estate gave way to allotments, which melted in turn into rectangles of gardens and then threaded into town: coffee chains, pubs, restaurants, a high street like many others. Leaving the station I avoided the centre, taking a residential road to the water meadows, and the last few cul-de-sacs bolted onto the outskirts.

Having left the town behind the first few minutes were eerily quiet. Then my ears recalibrated: the chatter of birds, the percussion of the trees that knocked branches and scraped leaves in the wind, a sudden explosion of beating wings as a blackbird took flight and the reassuring sighs of a wood pigeon hit me all at once, pushing out the last of the city.

This drover’s road was once an artery linking the hearts of the agricultural economy, but you’d never guess to look at it. Rutted and potholed, it’s now only of interest to walking groups, mud-splattered mountain bikers, lads racing through on motorbikes and those who get a thrill churning up mud and burning out the clutch on their 4X4s.

Stretching across Cranborne Chase the path runs almost parallel to the A30; the traffic was shuffling a few hundred metres away, the rough track above now almost forgotten. I wonder whose responsibility it is now to lay the gravel that lines the path and I’m grateful to them, for there’s no obviously practical reason. Maybe it’s an acknowledgement of the achievement of those who first trod this path. In this time of spiralling council cuts, perhaps, before long, it will be swallowed by the plants banked in either side, amassing strength and waiting patiently for the lapse of human attention to engulf the path and reclaim the earth once more, so that feet will never again be swollen by those hard won miles.

Like many old ways it runs straight, and favours the higher ground, the road folded across the crest of the hills like metal beaten over an anvil. Views sweep down one side of the incline into land left bare. For huge swathes of the walk the only mark of civilisation in sight were patchwork fields that evidence the hard work of the farmers; occasionally I saw their lonely dwellings marooned inside a sea of cultivated land, a tiny Land Rover parked outside, or a figure silhouetted on a hilltop.

The reminders that the world was close were subtle. A buzzard gliding and wheeling on the air currents waiting for an opportunity to dive at the carcass on the road below, or the vapour trails behind an east-bound plane.

The lush green of the valleys, the frequent clusters of woodland and rolling hills make up the most beautiful landscape that I know in Britain. It may not have the dramatic impact of the Scottish highlands or the nearly-mountains of the Lake District, but it has a rugged character of its own that seems quintessentially English. Despite growing up in its midst, the magic has never dissipated and during every re-exploration of this land, I find a new hidden delight. My map of the British Isles, sun-stained, stretched and pinned up on a door, shows areas of outstanding natural beauty as amorphous green blobs, and while most now have a tick of blue biro inside them, I still have yet to find one that can take the crown that I’ve placed on the brow of the hills in my homeland.

I had very little company. A pair of runners looping round an intersecting road, an empty car parked on the verge, and a man on a bike in a full-face helmet and a team jersey. Away from the thronged streets where your attention is demanded, my eyes wandered downwards: in the stripe of grass in the middle of the track I spotted caterpillars, inching along in the same direction. An exodus to some promised land of leaves or were they searching for some idyllic spot to cocoon themselves before their rebirth? Wildlife using roads as the path of least resistance has been well documented and I’ve seen animals following man-made tracks rather than fighting their way through the thick African bush; these minute travellers seemed stranger and stronger.

I passed paths that I’d never noticed before. It’s said to take years for a farmer to learn his fields, even in such a small area secrets are held back. I’d probably never know this path in the same way of those who forged it, walking this way for the livelihood, but I could at least know that my boots were playing a small part in keeping this way alive.

Buildings, pavements, streets and shops grew up around me as I walked to the centre of the village; dusk had fallen and apart from the glow of passing headlights it was deserted. I left my boots by the back door. I felt lighter, as if I had trodden the city’s worries into the ground, leeched into the soil. In a couple of months I’d be back; I’d walk that same path and hope that only the season would have changed.

Hugh Tucker is a travel writer from the South West of England. He lived and worked in South Africa before returning to London. He now lives in rural Wiltshire and writes about his travels, both close to home and further afield.

This piece was originally published on The Clearing, Little Toller’s journal about nature and place.